I’ve spent quite some time creating content online — mostly written. Essays, reflections, long threads that looked public but always kept me safely behind words. Writing was my way of thinking out loud, a reflective practice during years of inner exploration — something between therapy and philosophy, only more polished for public view.

Over time, I found myself among writers, seekers, and philosophers who live a peculiar digital life — small echo chambers of thought, orbiting quietly around the mainstream. There’s nothing wrong with that; such spaces have their place. But they exist on the margins, detached from the main human play — like a side show in the middle of the night that almost no one watches.

I sometimes wondered if it was the algorithm’s fault or simply the nature of what we do — slow thoughts in a world that scrolls fast. Maybe both. The attention economy rewards speed, certainty, and noise; I’ve always moved in the opposite direction. So while I was “online”, I was never really visible. Maybe I wanted it that way during my inner journey — to stay hidden, to speak without showing, to think without being seen.

Learning that being seen is part of the work

But something shifted. After years of living behind words, the need to embody what I’d been writing about started to grow quietly inside me. It wasn’t a marketing impulse or a strategic plan. It was simply the natural next step — to bring the invisible back into form, to move, to appear, to live.

I didn’t choose the form consciously — it appeared, as most real things do, when I stopped searching. Thought had led me as far as it could, and the rest had to be lived — in flesh, in time, in motion.

It all began just three months before my thirtieth birthday, when I decided to take a leap of faith with a hobby from childhood — and a life-saving tool of my early twenties — dance, or more broadly, movement. It returned to me exactly when I needed it: as a way to embrace physicality after nearly a decade of inner work, a way to connect both worlds.

The trembling courage of doing something visible

And somehow, I found the courage to follow it. I rented a professional 90-square-metre dance studio entirely for myself — not knowing what to do, of course, but knowing that I had to begin. The whole story of getting there deserves its own essay, because even a simple phone call triggered something close to a panic attack — and there was more. It might sound ridiculous, but it takes a surprising amount of courage to do something different at this age. Only people who have never tried would tell you otherwise.

Then — just a short moment later in adult terms — about five months after that first visit, I did it again, but this time in a smaller, more private studio. It wasn’t just a one-time visit, though still a short period overall. And since I had never played with visual content before — especially not the kind that included me — apart from three or four profile photos in my whole life, it felt difficult to capture anything from those sessions. But I wanted proof of my courage, a small reminder that I had done it.

When the digital mirror reflects something real

These events stirred a strange conflict inside me — a conflict of identities. For many years of my inner journey, I had been no one in social terms, living mostly in solitude. Before that, however, I had been someone to many people. Writing still fit that in-between state, but dance felt different — almost alien. I had been ashamed of it as a child and hid it throughout my teenage years. No, I did more than hide it — I pushed it out of my consciousness entirely. If not for photos and the stories my family told me, I wouldn’t even remember it.

And that’s how the little carousel with two photos of me in the studio — for most people, probably the meaningless post of a stranger — became a deeply symbolic act. It was more than a photo, more than a share. It grounded my identity after the inner journey — after I had reconnected with myself and was finally ready to tell the real story.

It’s worth keeping that in mind when browsing social media. Yes, I’m definitely an overthinker — maybe I reflect a little too much. But it’s not as if others mindlessly post themselves online either. Many are also terrified of how people might react. Maybe they’re grounding their identities, just as I was. Or maybe their simple share marks an important moment in their lives. It’s not always pure vanity.

Numbers can’t measure what it costs to appear

Anyway, the carousel performed terribly in terms of likes and reach — but it didn’t matter. It was my social rebirth, my first step after coming back to the cave, philosophically speaking.

A few months later, I had to replace my phone because it slowed down dramatically. An ordinary life event, but it came with two strange thoughts attached: a better camera and a bonus tripod. Somehow, I immediately saw them as tools to deepen my movement practice — and perhaps to explore video storytelling. I couldn’t escape the thought, so I accepted it, treating it as alignment with the flow, as the Taoists would say.

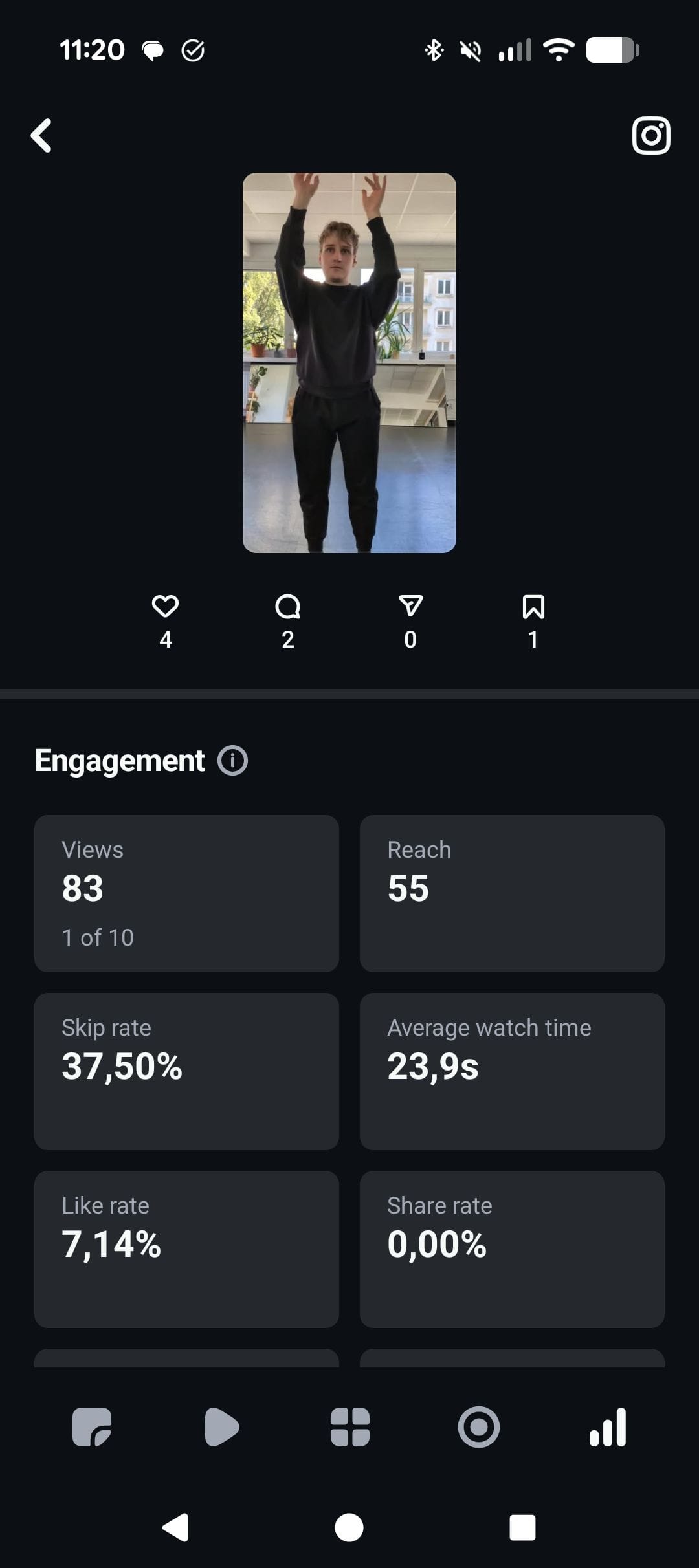

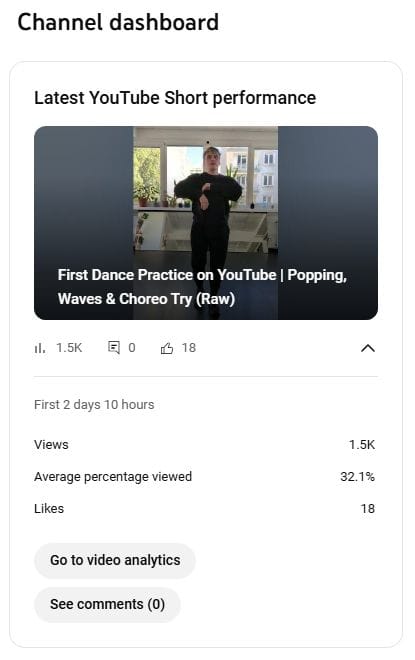

I bought the phone, found a new studio, and went there as if I were coming home — finally without the impostor syndrome. I stretched, unfolded the tripod, and began a session that later became my first reel on Instagram and, a day later, landed on YouTube Shorts. The reel performed even worse than the carousel before — it had literally five views when I went to sleep a few hours after posting. But that was fine. It was about alignment — the simple act of showing myself in movement for the first time.

I’m far too early in this visual journey to expect any real results, but I’ve already learned how random it all is. The same reel that barely moved on Instagram found a surprising reach on YouTube Shorts — the same movement, the same me, just different systems deciding what deserves to be seen.

Screenshots from Instagram Edits Reel Stats and YouTube Studio

But numbers can’t measure the trembling before pressing “record”, or the silence that follows when you do. That part stays the same for everyone.

Embodiment as the final form of philosophy

Anyway, I sometimes joke that this whole story is about a huge introvert learning how to leave the house — or to show himself — after years of hiding. But that’s not entirely true. I once heard a line I’ve remembered ever since: “If you have the courage to take yourself to a restaurant alone, you have the courage to do anything in life.” And with age, I think that’s true. Being alone in society feels like being a wounded animal — or one excluded from the herd — lost somewhere in the wild. And being alone in a dance studio at thirty, with moderate skills, recording yourself? It’s more than a restaurant.

I’m not writing this to announce how fantastic I am. I don’t care about that. I’m writing it because I wish I could have read something like this in my early twenties — a small blueprint for how to move imperfectly, awkwardly, honestly. We live in a world of perfect people, where vulnerability rarely makes it to the feed. And now, with AI polishing our photos, videos, and even stories, the illusion of perfection grows stronger than ever.

That’s one of the reasons I’ve been moving away from abstract philosophy and pure spirituality towards these diary-like essays. Because if you want to know about those topics, you can chat with an archive of humanity’s knowledge anytime you want. What that AI chat doesn’t have, though, are these little “fuck-it” moments — the doubt, the hesitation, the fragile courage it takes to appear.

Also, spirituality and philosophy have little value if they’re not embodied. You can stay online, hiding behind thoughts and borrowed language — posting about the “higher self”, the “new Earth”, or your latest manifestation ritual from a quiet room, surrounded by the same few believers.

But real spirituality — and real philosophy — begin only when you step outside and let life test what you claim to understand. Embodiment washes away the unnecessary noise. You can manifest dancing for years, but unless you walk into the studio, your body will never learn what your mind keeps repeating. Yes — no matter the affirmations or mantras you tell yourself.

And so I began this journey of clumsy embodiment. I leave it here as a small blueprint for all the misfits who dared to get lost — and are now wondering how to come back.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy my work and want more like this, consider supporting it. This space exists thanks to readers — essays and research take time. You can subscribe, contribute, or explore reading lists I curate. Every bit of support helps.