I always feel a little funny inside when I watch serious public debates about humanity’s “great role” on this planet. The way it’s framed, you’d think we were the central characters of the universe. Commentators praise our technology and responsibility as if human history were the pivot point of existence itself — anthropocentrism at its finest.

Most people seem to be so involved in social life that they no longer see any difference between social life and life itself. When they say “life,” they really mean the endless human show: our daily struggles, economies, the symbols we invented, the roles we play. And this is where the problem begins.

When we accept the flattering idea that humans stand at the center of everything, we disconnect from the living whole. Because such an idea is only an idea. The roles are only roles. The ego is only an image we project through personas. Meanwhile, the living reality goes on — the trees breathe, rivers flow, animals migrate, seasons turn. None of this waits for our permission. But in our heads, in our endless social chatter, we put ourselves above it all, as if the heartbeat of the planet were just a backdrop to our politics, our money, our little victories — an echo chamber where only our voices matter.

We build monuments to ourselves, give each other medals, write history books about who sat on which throne, who won which war, who made which fortune. But in the bigger story, these things are dust. A bee pollinating a flower does more real work for life than all the kings and billionaires combined. Yet we carry on as if the abstractions matter more than the soil under our feet or the air in our lungs, forgetting that without the living world, none of our games would even be possible. That’s the absurdity. That’s the disconnection.

When the human show replaces the living world

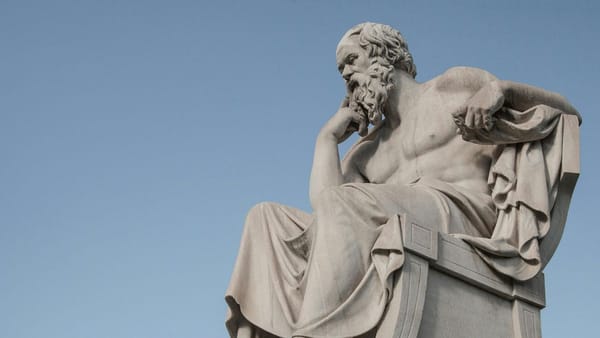

We live in symbols while forgetting life itself, like prisoners in Plato’s cave. And just as those prisoners don’t merely sit staring at shadows, but compete over who can name them best, we too turn illusion into a game of winners and losers. Power, wealth, status. What kind of nonsense is this? Well, it's a game, isn't it?

And when we start competing over abstraction, how much abstraction is enough? Is there some threshold of wealth or power? Some fixed number to reach? There isn’t. People consume abstractions like calories, counting digits, stacking numbers, measuring themselves against graphs, charts, and each other. But can you eat abstraction? Obviously not.

Yet history shows us the absurd hunger for more. No king or dictator was ever satisfied with the power he had — he always wanted more. The same is true of the stars of our era — billionaires. They already have enough numbers for a hundred lifetimes, but they still compete for more, fighting for the crown of who’s at the top of this year’s — or even this moment’s — wealth ranking.

The strange hunger for abstraction

Take Prince Alwaleed bin Talal from Saudi Arabia. In 2013, Forbes placed him as the 26th richest man in the world, with a fortune of about $20 billion. You’d think $20 billion would be enough for one person to relax. But no — he got furious, claimed the estimate was nearly $10 billion too low, and even severed ties with the magazine. Years later, he settled a libel suit against Forbes, proving how deeply he took the game.

Just think about that. A man who has more than he could ever spend in multiple lifetimes still storms off because his name isn’t ranked high enough on a scoreboard of abstractions. It’s like watching a child throw a tantrum in kindergarten because his drawing didn’t win first place. But here it’s not a crayon drawing — it’s billions of dollars, land, resources, real lives. And yet the ego still isn’t satisfied.

Which is the truly dangerous part: empty as they are, abstractions still bend reality because we believe in them. That belief gives them teeth. A piece of paper or a number on a screen is nothing on its own, but once the whole society agrees, it can command land, food, even lives. That’s the cruel joke: the symbols have no life of their own, yet they can reshape life when enough people worship them, as if shadows could command reality.

This is where the whole picture comes together. At the top, the game becomes absurd theatre, but everyone else still clings to their little piece of it. Why? Because from childhood, we’re trained to perform. Parents, teachers, peers — all hand us keys of indoctrination: be a good student, earn good grades, find a career, play the part. If you follow the script, you’re rewarded. If you don’t, you’re punished or ridiculed.

When adults forget it was only play

So, of course, people depend on their roles. Strip away the costume and they feel naked. Without the mask, they fear they are nobody. That’s terrifying. And so adults cling to their social games even harder than children would. Children laugh when the game ends; adults panic, because the game is all they’ve ever known.

That’s when we can discover how silly we are. Children at least know they’re playing when they pretend to be doctors or astronauts. Adults forget and consider this game the ultimate reality — something more important than life itself, and this is exactly where the danger begins, because once the play is mistaken for truth, people will sacrifice even life to protect the game.

Imagine a kindergarten where kids are playing “hospital.” One is the doctor, one is the nurse, one is the patient. Everyone knows it’s play. They giggle, they swap roles, and the game dissolves when the bell rings. Now imagine the same kindergarten, but suddenly the kids start demanding salaries, forming power hierarchies, and fighting each other to defend their little cardboard titles. That’s us. That’s adult life. We are children who forgot it was play and grew dangerous precisely because we take it so seriously.

And here’s the difference: children can afford to laugh when the game ends. But when adults mistake their play for ultimate reality, the consequences spill over into life itself. This is where the stakes rise: when the game of shadows becomes more important than life itself. History is full of examples. Aristotle once wrote that human beings are political animals, but he also warned that without virtue, we are the worst of all animals. Wolves kill to eat. Bees work to sustain the hive. Humans, trapped in ego and abstraction, destroy for the sake of symbols. We are the only creatures willing to sacrifice life itself — including our own — for the shadow on the cave wall.

The world that continues without us

The most dangerous part of this disconnection is that it gives us the illusion of control. We can manage statistics, currencies, laws, and narratives. But do you count every beat of your heart? Do you make the sun rise in the morning? Do you control photosynthesis? No. All the really important things just happen. And without bees and other pollinators, much of life on Earth would collapse in no time. But if all humans disappeared right now, nothing terrible would happen. The forests would breathe again, the seas would rest, the skies would clear. Life would continue in peace — without us.

So in that sense, we don’t matter. Our egocentric play is creative, yes, but also destructive. We mimic nature with technology and then pretend to be greater than nature itself. We tell ourselves stories, we hear voices in our heads, we invent imaginary crowns and titles, and then believe we’re the center of existence. It’s all tricks of the ego.

Maybe that’s the whole joke of it. We build thrones out of paper, fight wars over numbers, and crown ourselves kings of shadows. And all the while, the real world goes on without asking for our approval. The forests breathe, the oceans move, the bees work. Life continues whether we count it or not.

If there’s any hope, it’s that we can still notice this. That even for a moment we can step back from the festival of ego and laugh at how seriously we take the play. Not to stop playing — the play can be beautiful — but to stop mistaking it for life itself. And maybe that’s enough. To remember, even briefly, that behind every role and symbol there is a living world, quietly whole without us. A world we belong to, whether we play or not.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy my work and want more like this, consider supporting it. This space exists thanks to readers — essays and research take time. You can subscribe, contribute, or explore reading lists I curate. Every bit of support helps.