For a while now, I’ve noticed a strange, recurring tension in myself whenever I watch people we collectively call “authorities.” Public intellectuals, spiritual teachers, confident commentators explaining the world with impressive certainty. On the surface, everything looks coherent. The language is clean. The frameworks are well-structured. The conclusions feel reassuring. And yet, almost instinctively, something in me tightens. Not disagreement exactly — more like a quiet dissonance, as if I were watching a performance that works, but only because everyone agrees not to look too closely at what holds it together.

At first, I thought this reaction came from arrogance or overexposure. Maybe I had simply grown tired of grand explanations. Maybe it was another phase of skepticism. I even considered writing a sharp essay about how many of these figures are, in fact, deeply lost — children wrapped in symbols, mistaking confidence for clarity. But the more I sat with that impulse, the more it felt off. Not false, but careless. Because attacking the figures misses the more important question: why these structures exist at all, and why they continue to work so well.

What slowly became clear is that illusion isn’t merely a mistake people make. It’s something people rely on. Not in a philosophical sense, but in a biological one. Human beings don’t live on reality alone. We live on meaning — on narratives that organize time, effort, identity, and expectation. When those narratives hold, life moves forward. When they collapse suddenly, the effect isn’t enlightenment but disorientation and constant confusion.

Why certainty holds us long before it proves anything

I feel strongly about this, because in my case, the understanding did not emerge from theory, nor from slow intellectual refinement or fancy spiritual insight. It was forced into place by a single, sharply defined rupture — a moment when an entire theory of reality collapsed almost instantaneously. Not over years, not over months, not even over days. In the span of minutes, the underlying assumptions about how the world works were rewritten completely. It felt less like learning something new and more like being exposed to high voltage: disorienting, overwhelming, and deeply physiologically destabilizing.

When such a collapse happens that abruptly, what is lost is not comfort or optimism, but orientation itself. The future stops being navigable. Past effort loses coherence. Actions that once made sense no longer connect to outcomes. The nervous system reacts first — long before language or interpretation can catch up. It is not an insight. It is a shock.

Surviving that kind of rupture requires years of integration. Even with resources — intellectual capacity, philosophical grounding, contemplative practices, and some degree of external support — the process is barely manageable. Philosophy, spirituality, meditation, and disciplined inner work do not accelerate recovery so much as prevent total fragmentation. They offer containment, not resolution or closure.

Seen from this perspective, it becomes impossible to treat truth as something universally beneficial by default. If a single, unprepared exposure can destabilize a functioning system so profoundly, then the casual dismantling of other people’s meaning structures begins to resemble negligence rather than courage. What might look like “awakening” from the outside can, from the inside, feel indistinguishable from collapse.

When truth arrives faster than orientation can follow

At some point, this line of thinking inevitably drifts toward philosophy and spirituality — not as systems to believe in, but as lenses that quietly organize how experience is interpreted. It becomes difficult not to notice how much of human life unfolds inside structures that resemble Plato’s cave: shared narratives, symbolic hierarchies, roles mistaken for essence. These patterns aren’t subtle. They repeat across cultures, institutions, and personal lives with remarkable consistency over time.

What becomes less obvious — and more uncomfortable — is the assumption that dismantling these structures is automatically an act of care. There is a tendency to treat insight as a moral good in itself, as if exposure to truth were always proportional to freedom. But truth is not neutral. It behaves more like a force than a value. Without preparation, without context, without a container that can absorb its impact, it doesn’t clarify — it overwhelms. Instead of opening space, it floods it.

From this angle, the cave stops being merely a metaphor for ignorance. It begins to look like a psychological structure — one that protects, regulates, and stabilizes. Breaking its walls without understanding what they were holding back doesn’t produce awakening. It produces collapse.

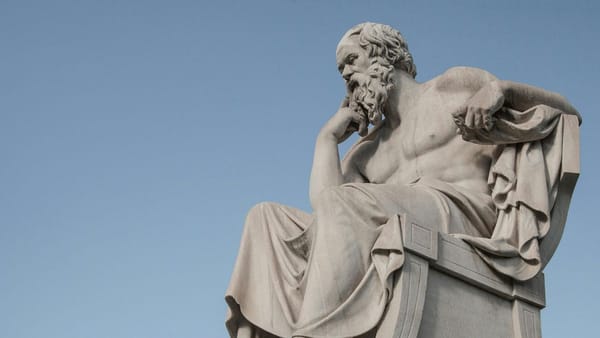

The ancients understood this intuitively. Socrates did not deliver answers; he asked questions — and even that proved too destabilizing for the city to tolerate. Plato did not write theories out of curiosity; he had nowhere else to put the trauma of watching a lawful society kill its wisest voice. The cave was not a cosmological model. It was a psychological one — a recognition that people defend their illusions not out of malice, but out of terror.

The same is true of the Buddha. His restraint was not mysticism; it was regulation. The stories where he withholds truth, answers obliquely, or even allows comforting distortions are not contradictions. They are acts of care. Because raw truth, delivered to an unprepared nervous system, does not liberate. It panics. It fractures. It burns out like a filament overloaded with current.

When meaning structures protect more than they deceive

This is also why the contemporary economy of spirituality feels so disturbing. The endless promises of awakening, the monetized urgency, the claim that a video, a course, or a book will “change your life.” This is not guidance. It is negligence. It sells high-voltage insight to unprepared systems, then calls the fallout growth. It preys on exhaustion, on longing, on people already destabilized by a world that no longer makes sense.

From this angle, even the way people consume ideas begins to look different. The preference for short videos, reassuring slogans, and promises of instant transformation is often interpreted as superficiality or intellectual laziness. But it can also be read as regulation. Content that claims to “change your life” without asking too much from the nervous system feels safe. It offers the illusion of movement without the risk of destabilization.

Deeper texts — the kind that don’t promise outcomes, don’t offer closure, and quietly undermine familiar structures — are easier to ignore. Not because they are unclear, but because they are precise. They don’t seduce. They don’t guide gently. They ask for readiness. And for many people, that request alone is experienced as threat. Avoidance, in this sense, is not indifference but an act of self-protection.

This recognition changes how illusion itself is understood. It stops looking like stupidity or weakness and begins to resemble protection. For most people, statements like “I am a parent,” “I am a worker,” or “I am this kind of person” are not philosophical claims. They are regulatory anchors. Remove them, and what follows is not clarity, but existential free fall — often followed by aggression, because threatened systems defend themselves.

The COVID pandemic made this visible at a collective scale. When routines, roles, and external structures were abruptly suspended, the result was not greater clarity about life or values. It was widespread psychological destabilization. Anxiety, depression, derealization, aggression, and exhaustion spiked across societies. Not because people suddenly “saw the truth,” but because the frameworks that quietly regulated daily existence were removed faster than anything could replace them.

The experience was unpredictable, prolonged, and opaque. It offered no coherent narrative to integrate, no stable endpoint to orient toward. In that vacuum, many people did not become more conscious. They became more fragile. The experiment was unintentional, but the outcome was clear: when meaning structures collapse suddenly, the nervous system does not awaken — it scrambles to regain stability.

Seen from this angle, the tragedy of Socrates becomes inevitable rather than accidental. He was not killed despite being right. He was killed because he was right — and because he offered questions without replacement structures. Plato understood this. That is why he retreated into dialogue rather than proclamation. Dialogue does not force truth. It filters for readiness. It protects both the speaker and the listener.

What emerges from all this is a strangely liberating conclusion: not everyone should leave the cave. Not everyone can. And not everyone needs to. The task is not to wake the world. The task is to live truthfully without turning truth into a weapon. To help only those who are already searching. To leave traces rather than proclamations. To answer questions when they are asked, not before.

Sometimes the most compassionate act is a smile, a nod, letting someone win a game they need to win. Not out of condescension, but out of care. Because it’s possible to see when an illusion is holding someone together — and when breaking it would not make them freer, only lost.

If there is a role left for those who have seen through the structure, it is not to dismantle it. It is to move within it lightly. To embody regulation rather than revelation. To allow truth to breathe through form — through presence, movement, rhythm, and ordinary life — instead of forcing it through language alone, stripped of context.

It is no necessary to wake anyone up. It is enough not to fall asleep. To know when to speak, and when silence is protection. To recognize that illusion, for most people, is not the enemy — it is the skin that keeps the organism alive in a world that would otherwise be unbearable.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy my work and want more like this, consider supporting it. This space exists thanks to readers — essays and research take time. You can subscribe, contribute, or explore reading lists I curate. Every bit of support helps.